Kagan's Articles - FREE Kagan Articles

Research & Rationale

Ten Years Later

Special Article

Ten Years Later

Personal Reflections on Returning Home

Dr. Vern Minor

To cite this article: Minor, V. Ten Years Later: Personal Reflections on Returning Home. Kagan Online Magazine, Issue #58. San Clemente, CA: Kagan Publishing. www.KaganOnline.com

Not long ago I had the good fortune of returning home to conduct a USA Tour event. I think of Hesston (KS) as home on occasion even though I was not raised there. I was, however, blessed to have served the community as their superintendent of schools for twelve years. In superintendent years, that is a lifetime. So, while I have no relatives residing there, it still feels a bit like home to me.

I have been gone from the district for ten years. Though I have stayed in touch with a few folks in the organization since my departure, I had not set foot back in the district until recently. I thought it best for those leaders who succeeded me to keep my distance. If you have ever followed someone who held your leadership position for many years prior to your arrival, you know exactly what I mean.

Since my departure every member of the administrative team with whom I served has also left the organization. Hesston is a small K-12 school district, so even the departure of a single leader can have a significant impact. In this case all central office and building level administrators left in the years following my exit, each choosing to pursue other leadership opportunities. No one from the team of which I was a part remains.

The teaching ranks have also changed over the last decade. As I stood before the staff in preparation to present, I looked out over the sea of faces. I recognized several—a few more wrinkles for some, sprinkles of grey for others. A couple of former students have been hired as teachers, which did my heart good. However, there were many staff members I had never met.

With all this in mind, I wondered. How much had the district changed in a decade? What direction were they now headed? Were initiatives from the past still pervasive? The primary focus during my time in the district was on student engagement. We embraced the premise that engaging all students all day long with academic content and with each other would narrow achievement gaps. Our initiative was student engagement, our strategy for engaging students was cooperative learning, and the training model we chose was one created by Dr. Spencer Kagan. Ten years—what remained intact?

I was intrigued to learn that nearly every system that had been initiated years before remained. Processes related to curriculum alignment, data analysis, learning intervention, time management, professional development—all were alive and well. Granted, some systems had been tweaked and a few new ones introduced, but by and large, reform initiatives launched many years before had stood the test of time. Most interesting of all to me was the district’s continuing commitment to student engagement. Hesston is comprised of a team of educators who have embraced what John Hattie concluded in his research when he noted, “It is what teachers get students to do in the class that emerged as the strongest component of the accomplished teachers’ repertoire… Students must be actively involved in their learning” (Hattie, page 35).

How is it possible after ten years, a complete change in the leadership team, and the overhaul of a significant portion of the teaching workforce that cooperative learning still remains as a central component of their school improvement efforts? We know that “…initiative fatigue is a serious and growing problem” (Reeves, 2011, page 1) in American schools. We are notorious in our business for changing directions and adopting new initiatives every couple of years. So how has Hesston, in the absence of those who launched the initiatives, been able to maintain key initiatives a decade later?

There are actually several reasons. In the course of this article we will explore three key explanations. Before doing so, however, let’s take a glimpse at the student achievement results that were attained. This will be critical to our understanding of why cooperative learning is still prevalent in the organization to this day.

THE DATA

All educators know that research should undergird any change in an organization. The days of chasing a program to solve our woes have long since passed in school improvement. “If we have learned anything in our research it is that practices endure while programs fade” (Reeves, 2011, page 8). However, even when the research is overwhelmingly convincing, many times we struggle to adopt it. There is a radical difference between knowing what the research says and putting that research into practice. Hattie found that to be true when he remarked, “Why does this bounty of research have such little impact?” (Hattie, page 3).

Cooperative learning is the most researched educational innovation of our time (Kagan & Kagan, 2009). During my tenure in Hesston, we read the research before we entered into training, and we understood the possible positive ramifications of utilizing this pedagogical method. However, in the early stages of implementation, I am not sure we truly embraced the research. Then something magical happened. When we put our newly learned strategies into operation, our assessment data changed.

Hesston was not broken, not by any stretch of the imagination. For many years students had been afforded a wonderful educational experience. However, moving from very good to great is not an easy undertaking. For one, there is not as much room for improvement when compared to settings that have serious learning challenges. Additionally, it’s quite easy to become satisfied with the status quo when things seem to be rolling along smoothly. Nevertheless, the staff agreed to give cooperative learning “the old college try,” and when they did, the data surprised us all.

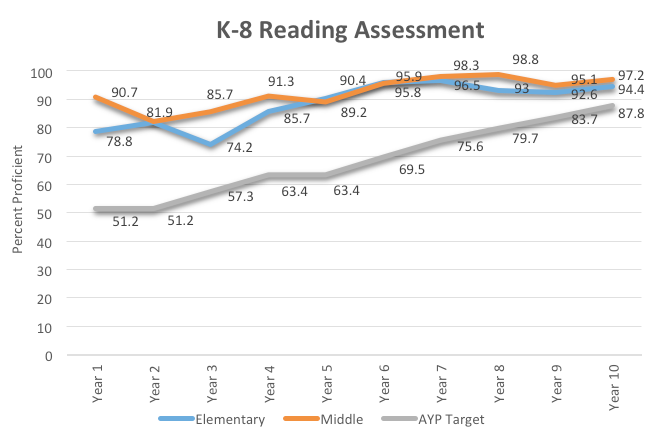

Finding assessment data that lends itself to trend comparisons is difficult. Assessments (local, state, national) seem to be in a constant state of flux. Nevertheless, our state assessments during my tenure stayed relatively static for a ten year time period, allowing us to look at trends over time. Included below are four graphs (i.e., two for reading and two for mathematics) which highlight the district’s progression on the percentage of students reaching proficiency on state assessments. Additionally, AYP benchmarks established at the time by the state department of education are also included.

As noted above, this district was achieving at very good levels when we began implementing cooperative learning. However, there was clearly room for improvement. We took seriously the charge to ensure all students learned at high levels. A district that truly embraces “all” does not remain satisfied with 75% of students reaching proficiency. The only number that can be acceptable is 100%. While we did not quite hit the target, all four of these snapshots show trend lines steadily pointing upward toward 100%.

Furthermore, the state department of education during this time period annually recognized districts that performed at high levels. Such districts received the distinction of Standard of Excellence (SOE). Highlighted below is a summary of the district’s performance over twelve years (ten of those coinciding with the graphs above).

|

Standard of Excellence |

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Year 4 |

Year 5 |

Year 6 |

Year 7 |

Year 8 |

Year 9 |

Year 10 |

Year 11 |

Year 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tests Taken |

6 |

12 |

6 |

12 |

6 |

12 |

14 |

17 |

20 |

20 |

17 |

17 |

|

SOE Achieved |

2 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

10 |

12 |

13 |

16 |

15 |

13 |

13 |

|

Percent |

33% |

25% |

50% |

33% |

67% |

83% |

86% |

76% |

80% |

75% |

76% |

76% |

As the number of tests grew over time, so did our performance. We began by achieving SOE on only one-third of assessments given; eventually we were regularly receiving SOE on 75-80% of all assessments given. I vividly recall the first time when 100% of students in a given grade level reached “Proficient or Above” on an assessment. Our staff was shocked. We had talked about hitting 100% on occasion, but I am not certain we ever truly believed we could accomplish it. Once we reached that plateau, staff commitment changed. Our data built momentum; the research we had read took on new meaning. We became convinced that student engagement was critical to success, and the use of cooperative structures skyrocketed.

This belief—student engagement enhances achievement for all—became rooted in the culture of the organization. Everyone associated with the organization—leaders, teachers, board members, parents, classified staff—witnessed firsthand the impact of engaging students through cooperative structures. This helps to explain why the district has been able to maintain a common direction even though leaders have come and gone. The research combined with our own data convinced Hesston educators to embrace the initiative.

The district’s data remains strong today and continues to reinforce the conviction to maintain the current direction. However, this commitment to engagement did not happen overnight. There were significant matters that had to be addressed to ensure that teachers stayed with the initiative long enough to impact student data. Too often educators do not employ a strategy long enough for student data to be positively affected. As a result, pedagogical initiatives come and go. Hesston made sure that did not happen by addressing the three key issues highlighted below.

FOCUS

“When everything is important, then nothing is important” (Reeves, 2011, page 36). What a powerful, true statement. When districts continually shift directions in their school improvement efforts, little is gained. We suffer, as noted earlier, from what Douglas Reeves describes as initiative fatigue.

Initiative fatigue is the tendency of educational leaders and policymakers to mandate policies, procedures, and practices that must be implemented by teachers and school administrators, often with insufficient consideration of the time, resources, and emotional energy required to begin and sustain the initiatives (Reeves, 2011, page 1).

According to his research, only 0.57% of schools have focus in their school improvement efforts (Reeves, 2011, page 5). Reeves accurately described what is transpiring in countless districts around the country.

The greatest challenge is that too few initiatives ever achieve the highest level of implementation…Rather than reach the highest levels of achievement, school leaders and teachers unanimously claim, “Well, that didn’t work, so let’s try another initiative.” Thus, schools are littered with initiatives that they start but never completely implement (Reeves, 2016, page 34).

Reeves is not the only researcher to support this claim. Fullan and Stiegelbauer noted, “The problem is not resistance to innovation, but fragmentation, overload, and incoherence resulting from the uncritical and uncoordinated acceptance of too many different innovations” (Fullan & Stiegelbauer, page 197). To be quite frank, we don’t need research to understand this concept. Ask any educator you know, “Does your organization suffer from initiative fatigue?” The answer will be a resounding, “Yes!”

—Douglas Reeves

Before we start placing blame and casting stones, let’s understand that this is to be expected in an age of reform. Young leaders who are reading this article need to realize that having access to educational research is a relatively recent phenomenon. I have been in education for nearly four decades. When we started the school improvement process in the late 1980s, we had very little research on which to draw. So, while it is true that we now know “what works best” (Hattie, page 18) in order to narrow achievement gaps, that has not always been the case.

As such, as research revealed best practices, leaders became aware of what needed to change, and they introduced new initiatives into their organizations. New research produced new findings, which produced new initiatives. Research accelerated over the past two decades, each time revealing what needed to be changed in the areas of curriculum, assessment, and instruction. The need to stay current resulted in a wave of new innovations in districts. Initiative fatigue has not necessarily been created as a result of poor leadership; in many cases, it is quite the contrary. It simply is part of school reform—the more we have learned about what works to narrow gaps, the more change we have introduced into our respective organizations.

Having said this, what we have simultaneously learned along the way is that “…focus is a prerequisite for improvement” (Reeves, 2011, page 3). Michael Fullan noted, “When it comes to change, less is more” (Fullan, page 16). We cannot continue to shift directions every two years and expect anything to change. We understood this at Hesston, so a critical decision made many years ago was to have focus. We did not jump on every bandwagon that came along. We hung our hat predominantly on a single focal point—engage every child every day all day long. Without a doubt, this focus is a foundational reason why the district has been able to maintain their commitment to cooperative learning for so many years.

Before leaving this concept, let’s make sure we grasp one very important fact. While it is true that without focus “…even the best leadership ideas will fail” (Reeves, 2011, page 3), focus is not enough. If a district chooses to concentrate on the wrong initiatives, gains in student learning will not occur. It is critical that we focus on what will make the greatest impact on learning. Hattie discovered during his examination of school improvement strategies, “Everything seems to work in the improvement of student achievement… even though the variability of what works is enormous” (Hattie, page 6). Fortunately for Hesston, the focus on student engagement was a sound decision, for “…it is what learners do that matters” (Hattie, page 37).

IMPLEMENTATION

I have held a longstanding difference of opinion with a colleague of mine regarding change. She contends that the most difficult aspect of change is launching a new initiative. I maintain what is most challenging is sustaining a change. If the truth were known, we are probably both correct. However, when I have shared with fellow leaders how innovations have been maintained in Hesston for ten years following the departure of the initiators of these changes, all have been astounded. A second key factor in making this happen was the resolve to support implementation.

We have known for decades that support systems are critical for successful implementation. Bruce Joyce and Beverly Showers discovered in their research from the late 1980s that a transfer of training problem exists if all we do is send teachers to training (Joyce and Showers, 1988). I continue to be amazed at the number of leaders who send teachers to training, hoping they will implement. Training does not narrow achievement gaps; implementation of research-based strategies narrows achievement gaps. Leaders must understand that “…incremental change does not result in comparable incremental gain in student achievement. Rather the greatest gains in achievement happen only at the greatest levels of implementation” (Reeves, 2016, page 32).

Support systems ensure teachers implement with fidelity and frequency. Without systematic support teachers may unknowingly implement initiatives in a faulty manner. Hesston put systems in place—and have continued them to this day—to ensure teachers implemented cooperative learning effectively. A partial listing of these supports is listed below.

- Kagan Coaching

- Structure-A-Month Clubs

- PIES Analyses

- Walk-Throughs

- Peer Observations

- Implementation Rubrics

- Lesson Planning

- Cooperative Meetings

“Communication during implementation is far more important than communication prior to implementation” (Fullan, page 26). Each of the support systems noted above is rooted in structured peer interaction. Installing these systems has benefited Hesston in numerous ways: (1) clarified expectations; (2) provided differentiated support; (3) imposed subtle pressure on the most uncertain; (4) enabled troubleshooting to take place; and (5) strengthened peer collaboration. In short, the cumulative effect of multiple systems ensured teachers were implementing the strategy effectively. When that happens on a widespread basis, student learning is impacted.

INSTITUTIONALIZATION

Focus helps us narrow our improvement efforts. Support systems enhance the likelihood that implementation occurs with fidelity. Institutionalization ensures the change is longstanding. Unless efforts are made to institutionalize the change, initiatives will always be connected to people. When that happens, initiatives will come and go as people come and go in the organization, and that creates fatigue. The way to avoid this is to embed the change in the culture of the organization.

“Probably the most important—and the most difficult—job of the school-based reformer is to change the prevailing culture of a school…” (Barth, page 7). Few would argue this, but it is possible to impact the value systems of an organization. Hesston took very intentional steps toward ensuring that cooperative learning became institutionalized. Three specific strategies that were part of that entrenchment process are noted below.

The first involved a key group of people—the board of education (BOE). From the beginning the BOE was involved in this initiative in a variety of ways, including the following: (1) reading the research; (2) visiting classrooms; (3) discussing the topic at board meetings; (4) experiencing structures in retreat settings; (5) listening to testimonies from teachers and students; and (6) attending training. They became well-versed in the research and data associated with the strategy.

As a result, the BOE became convinced this was a component of education they wanted for the children of the community. To solidify that commitment, they took an important step by embedding language related to student engagement and cooperative learning in the district’s guiding documents—board policies, district vision statement, district mission statement, collective commitments, and employee handbooks. There was no doubt regarding the BOE’s expectation—if you wanted to work in the Hesston School District, student engagement was an expectation. That expectation continues to this day.

The second strategy that was important to making sure this change was longstanding was the new teacher induction program. When vacancies occurred, applicants who had cooperative learning training in their background received preference. During interviews prospective teachers were asked about their views on cooperative learning; teachers who did not value student engagement were not hired. If they had not already done so, new employees were also required to complete the foundational five days of Kagan Cooperative Learning training (i.e., Level I). Additionally, all new teachers were coached frequently during their first two years. The new teacher induction program was the means by which maintenance of effort took place.

Finally, one last method by which cooperative learning established itself in the culture of Hesston was how it permeated the entire organization. We did not value just student engagement; we valued engagement. Making sure “all” were engaged did not just pertain to the classroom; it was equally relevant to faculty meetings, board of education retreats, community task forces, and classified employee meetings. Cooperative meetings became the norm for how we did business with adults. We invested in relationship building, professional dialogue, and shared decision making. As adults experienced for themselves the power of structured interaction—as they felt what it meant to be truly engaged—they became committed to ensuring that this initiative did not disappear over time.

FINAL THOUGHTS

My favorite movie is The Wizard of Oz. One of the most famous lines from that movie is expressed near the end when Dorothy exclaims, “There’s no place like home.” I have had leaders from other organizations tell me that what has been achieved in Hesston is unique (i.e., there’s no place like Hesston). I do not believe that to be the case. Don’t get me wrong; I am exceptionally proud of Hesston’s current leadership team and staff members for their continuing commitment to student engagement. They are a remarkable group of educators. However, what this educational team has accomplished the past two decades can be replicated. Decisions that were reached, commitments that were made, and systems that were instituted can be duplicated in any district, regardless of size.

Nearly seven decades ago, Ralph Tyler, regarded by many as the father of educational evaluation and assessment, advocated, “Learning takes place through the active behavior of the student; it is what he does that he learns…” (Tyler, page 63). If we ever hope to narrow achievement gaps, it is crucial that we focus on the “…smallest number of high leverage, easy-to-understand actions that unleash stunningly powerful consequences” (Fullan, page 16). Cooperative learning is such a strategy. Hesston simply chose to embrace this.

There will never be a substitute for student engagement. Regardless of what comes down the pike in the realm of reform, student engagement will never go out of style. It is possible to create an organization where every child every day is fully engaged. It takes focus, it requires being committed to implementation, and it entails institutionalizing the change. When that happens, we achieve what Rick DuFour had in mind when he noted, “Educators are being called upon to do something that has never been done before… to ensure high levels of learning for each student” (DuFour, page 192).

I am clearly on the downhill side of my career. While I am certainly not ready to call it quits, I’m not so naïve as to think that I will work forever. I have a few good years left in me, but I know the time is coming when I will hand the leadership baton to the next generation. I am confident that I will look back on my career with many fond memories. One of the most satisfying memories for me will be remembering how the changes a team of educators launched years ago continue to this day.

References

Barth, R. (1991, October). Restructuring schools: Some questions for teachers and principals. Phi Delta Kappan, 73(2), 123-128.

DuFour, R. (2004). Whatever it takes. Bloomington, IN: National Education Service.

Fullan, M. (2010). Motion leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Fullan, M. & Stiegelbauer, S. (1991). The new meaning of educational change. London: Cassell.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Joyce, B. & Showers, B. (1988). Student achievement through staff development. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Kagan, S. & Kagan, M. (2009). Kagan cooperative learning. San Clemente, CA: Kagan Publishing.

Reeves, D. (2011). Finding your leadership focus. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Reeves, D. (2016). From leading to succeeding. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Tyler, R. (1949). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.